There are many versions of Resolute’s story cropping up on the internet these days, many of which contain significant errors. Therefore, I’m offering her concise story here, which is based primarily on my original research, conducted in both America and Britain, using primary sources.

IN 1845, Sir John Franklin departed Britain with two ships, HMS Erebus and Terror. His remit was to find the elusive Northwest Passage through the Canadian Arctic. By 1848, when the Admiralty hadn’t heard from or about Franklin for 3 years, Beaufort began looking for him and his men. Eventually many others, from both Britain and the United States, joined the search. (These searches, for both the Franklin Expedition and the Northwest Passage, have been covered many times by excellent maritime historians. Therefore, there’s little need for me to rehash this part of Resolute’s story. Sources for this will be on my bibliography page.)

One of the first officers sent to look for the Franklin men was Henry Kellett, on HMS Herald. He’d been surveying in the Pacific Ocean when the Hydrographer to the Navy, Francis Beaufort, pulled him off this work and sent him up into the Bering Strait to look for any signs that the Franklin Expedition had made it through Canada. At the same time, Beaufort sent two ships, Enterprise and Investigator, into the Eastern Arctic under the command of James Clark Ross. This was Beaufort’s first two-pronged approach to searching for the Franklin Expedition, a technique he would use again. When these first attempts to find the Franklin men were unsuccessful, Beaufort began organising a second, two-armed search.

This time, planning to send Enterprise and Investigator into the Canadian Arctic from the West, he needed to buy more ships. In quick succession the Admiralty bought two sailing vessels: Ptarmigan (renamed Resolute) and Baboo (renamed Assistance). Being an advocate of steam, Beaufort rounded out the Admiralty’s buying spree with two steam tenders: Eider (renamed Intrepid) and FreeTrade (renamed Pioneer). The combination of sail and steam proved so beneficial that two years later, after again having no success finding the Franklin men, Beaufort sent the same four ships into the Arctic again. He added the North Star as a depot ship, and placed the new expedition under Edward Belcher.

The officers in command of the Belcher Expedition’s five ships were:

Captain Sir Edward Belcher, squadron leader

Commander George Richards, HMS Assistance (Belcher’s flagship)

Captain Henry Kellett, HMS Resolute

Commander William Pullen, HMS North Star

Lieutenant Sherard Osborn, HMS Pioneer

(promoted, Lieutenant Commander, October 1852)

Lieutenant Commander Francis Leopold McClintock, HMS Intrepid (McClintock was the man who eventually found the definitive proof of Franklin’s death when he was later the captain of the Fox.)

Admiralty records show that Belcher was a sadistic man who earned his nickname “Hell Afloat” many times over. His diametric opposite was Henry Kellett. A kind and respected officer, Kellett made his men feel integral members of his team, showing them he trusted their judgement and experience. Kellett’s steady and extremely competent second in command (on steam tender HMS Intrepid) was Lieutenant Commander Leopold McClintock.

Originally meant to search the eastern reaches of the Canadian Arctic together, the Belcher Expedition split to incorporate searches for the Enterprise (Collinson) and Investigator (McClure). Neither had been heard from since they entered the Arctic from the west in 1850.

Belcher’s North Star stayed at Beechey Island as a depot, and the rest of the squadron split: Assistance and Pioneer traveled north up the Wellington Channel under Belcher’s command. Kellett took Resolute and Intrepid west, to make for Winter Harbour, Melville Island, where Parry had camped in 1822. Although able to get close to their destination, they couldn’t quite make it into Winter Harbour. Instead they stopped at Dealy Island and setup their winter camp. They cut a dock in the land ice to protect the ships from the floe ice, and built the snow and ice up around the sides of the vessels for insulation. The yards and masts were taken down, except for the lowest sections of the masts. The men used these to make a tent over the deck, so that they would have a protected place to exercise when the weather was so bad that they could not go out on the ice.

While these preparations were ongoing, Kellett sent Resolute’s autumn sledging parties out over Melville Island, creating cairns of supplies, so that when the spring came, they would be able to search as far as those cairns, and then that much farther again. It was during this autumn activity that Mecham discovered a cairn containing information from Captain Robert McClure, (HMS Investigator). McClure gave his location and information they had been frozen in the ice for 2 years. When Mecham brought this news back to Resolute, the men wanted to sledge to Investigator right away to help them. But Kellett knew it was too late in the season to responsibly send men out when winter storms were likely to cause casualties, so he ordered the Resolutes and Intrepids to stay in camp. He did, however, make McClure his top priority for the spring.

The men came to the Arctic prepared for the long, dark winters. They brought with them books, musical instruments, and sailors’ sense of fun and adventure. George Frederick McDougall, Resolute‘s Master, was central in setting up Resolute’s Arctic Theatre Royal, which gave 2 performances during the first winter. Kellett, in keeping with being interested in the welfare of his men, was in charge of the theatre committee, while others organised a lecture series.

From the winter camp of HMS Resolute and HMS Intrepid, just off Dealy Island, the men depart on their spring 1853 sledging trips. During the course of 1853 many of them completed record breaking trips.

In the spring of 1853 Kellett’s sledging parties fanned out, with Lieutenant Pim setting off for McClure and the Investigators. Once found, Kellett determined through his surgeon Domville’s medical examination that there weren’t enough Investigators healthy enough to stay another year on Investigator, and he ordered McClure to abandon his ship. The Investigators joined the Resolutes and Intrepids for the remainder of the time they spent in the Arctic searching for Franklin. During the winter of 1853-4 Resolute and Intrepid weren’t able to make camp in the stationary land ice because a sudden drop of temperature froze the water around the ships. However, they did cut docks into the floe ice, which moved very slowly towards the east throughout the winter.

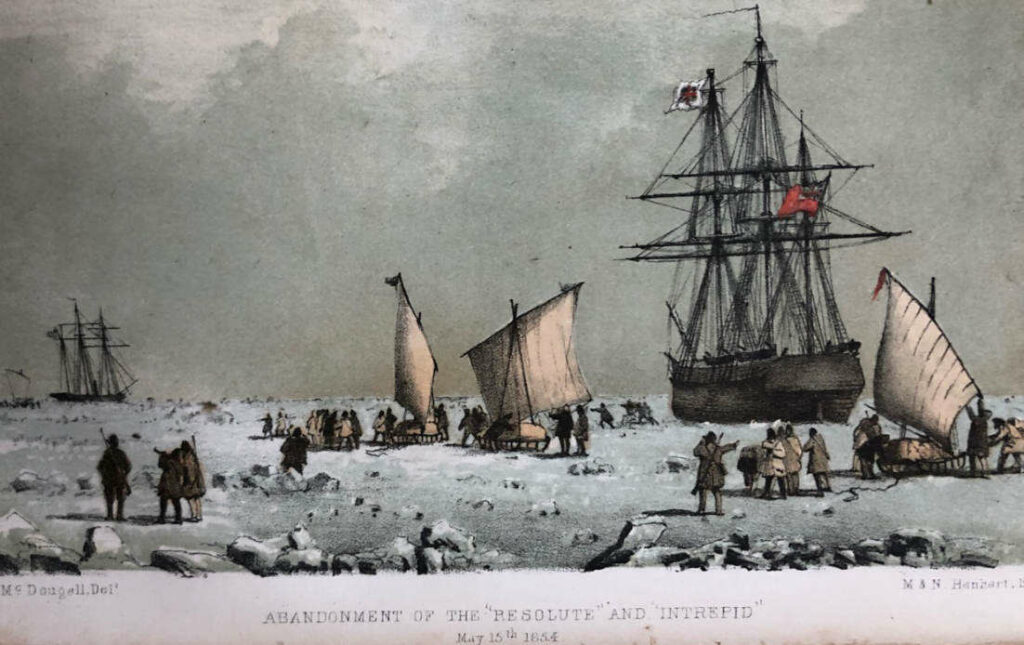

Meanwhile, conditions on HMS Assistance and Pioneer deteriorated steadily. (I include details of just how bad things got in my new manuscript.) In the spring of 1854 Belcher wrote a private letter to Kellett suggesting he abandon his ships. Kellett refused. Twice. Even though he had 3 ships companies on 2 ships, he had plenty of food because he’d encouraged his men to hunt whenever possible. Additionally, his men were in good health (even most of the Investigators), and the ships in good shape, so he didn’t feel justified in abandoning them. After Kellett’s refusals Belcher finally sent a public letter (not marked as private) containing a written order. Kellett could not refuse, however, he only abandoned his ships under protest. All the Resolutes, Intrepids, and Investigators sledged to Beechey Island, where North Star was stationed. Luckily, two additional supply ships arrived in August just as they were all preparing to leave on North Star.

The Assistances, Resolutes, Pioneers, Intrepids, and Investigators all made it back to Britain safely.

There is not enough room in this summary to go into the courts martial that took place (as a matter of routine when a ship is lost) when the men returned to Britain, suffice it to say, all were acquitted by the Admiralty for abandoning their ships. The judges commended Kellett for his diligence, but shamed Belcher by returning his sword to him in cutting silence. Finally, after a naval career marked by its sadism and cruelty, Belcher never received another active commission from the Admiralty.

I cannot go into the complex political situation which existed between America and Britain in 1855-56. I have too much hard-won research involved! But I can say things were very tense for a number of reasons. In September 1855 Captain Buddington, from the New London, Connecticut whaling firm Perkins and Smith, was whaling in the Baffin Bay area onboard George Henry. When his lookout saw a ship in the distance Buddington hailed it, but got no response. Subsequently he sent several George Henries across to investigate. They discovered the deserted ship was Resolute. She was 1,200 nautical miles from the place of her abandonment, but still sea-worthy!

An abandoned vessel was worth quite a bit of money as salvage, much more than Buddington would have made if he had a full hold of whale bone and oil. This was something he most decidedly did not have thus far on this trip! It took the George Henries a week to pump the 7 feet of water from Resolute’s hold, and find enough good sail to rig the courses. Buddington then split his crew, and took onboard Resolute 13 men, a faulty compass, his watch, an outline of the North American coast he’d drawn on foolscap, and his years of experience and sailed for New London. The ships got separated rather quickly even though they had hoped to sail home together. Storms forced Buddington almost all the way down to Bermuda before he could head towards New London again. The George Henry got home first. Resolute arrived at Groton, Connecticut on Little Christmas Eve (23rd) and crossed the Thames River to New London on Christmas Eve. By the time she anchored, the dock was full of New Londoners carrying torches to welcome Resolute to their hometown.

The relationship between Britain and America was truly at the breaking point; but, early in 1856, Her Majesty’s Government waived their rights to Resolute, and Buddington and the George Henries suddenly found themselves owners of a Royal Navy exploration vessel…but not for long!

That summer Virginia’s Senator Mason presented a joint bill to Congress, proposing the government buy Resolute from Perkins Smith, refit her like she was brand new, and sail her back to Britain as a present. This was particularly astonishing because Mason had been one of the most vocal warmongers in the Senate. He clearly had a change of heart! During recent research my husband (and excellent research assistant) found substantive proof of how this change of heart came about. All I am willing to say here is that it was not above board, by any stretch of the imagination. In fact, no stretching is required at all. But you will have to buy the new book to find out what this proof consists of! Eventually, both houses of Congress approved the resolution. Resolute when to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, where she was refitted to the highest standard. The United States Navy’s southern officer, Captain Henry Julius Hartstene, sailed her back to Britain. After Queen Victoria graciously accepted the gift, all the talk of war began to recede.

In 1879, when Resolute went to the breaker’s dock at Chatham, several desks were made from her timbers. The most famous one is in the Oval Office. Queen Victoria asked for a small writing table to be made for her private yacht, and I was fortunate enough to use it for my lecture and book signing at the Royal Navy Museum, Portsmouth in February 2008.

Needless to say, several accounts about the desks on the internet are incorrect. Surprisingly, even the White House has the designer and maker wrong in their brochures! The designers and makers of the other desks are incorrect throughout as well, which are amongst the facts in the Resolute story that I correct in my non-fiction manuscript.

The nutshell about the White House’s Resolute Desk is this: After it arrived at the White House it lived in various rooms. President Kennedy was the first president to use it in the Oval Office, and Presidents Carter, Reagan, Clinton, G W Bush, Obama, Trump, and now President Biden have also used it in the Oval Office. A smaller desk made for Henry Grinnell’s widow is in the New Bedford Whaling Museum, New Bedford, MA.

This story is significant for several reasons. Absolutely uniquely in maritime history Resolute is the only ship abandoned in the Arctic to survive, not to mention then travelling around 1,200 miles through the ice, without getting crushed. This part of her story is interesting enough. But Resolute went on to become a gesture of goodwill and peace when one was desperately needed to avoid war.

Britain and the United States have settled their differences ever since through diplomacy, not war. Eventually, after becoming firm allies, their relationship most definitively changed the course of 20th century history.