I mentioned earlier that Barnard Colby’s For Oil and Buggy Whips, (Mystic, Connecticut, Mystic Seaport Museum, Inc.) 1990, is an excellent book on the whaling captains of New London, Connecticut. I used it as a source for the background on the men involved in forming Perkins and Smith, the whaling firm Buddington worked for, and as one of my sources for the history of the New England whaling industry. I also used it as one of my many sources about Buddington’s 1855 voyage on the George Henry and the circumstances surrounding his discovery of HMS Resolute in Davis Strait. My more recent research, however, has shown his account to be quite wrong, although I must stress that his research on the rest of New London whaling is very good. On page 78, Colby begins recounting Buddington’s voyage by saying he left New London on 20 May, my research shows he departed on May 29th. Having begun the trip on the wrong date, Colby’s dates get consecutively worse throughout his account on pp 78-79. He mentions the damage the George Henry sustained 16 days into their trip, which I also have, but in my ms this date is 14 June, then I agree they headed to Greenland for repairs. He then says, after their repairs, still in June, they caught whales is Disco Bay then headed home. Buddington wasn’t actually headed home quite yet, and he wasn’t in Disco Bay until 31 July. The following is what really happened with the George Henry before finding Resolute. (an excerpt from my new ms:)

“Five days along the pack, on the 19th [June], quickly moving, sharp-edged flow ice severely mangled the George Henry’s cutwater (the forward edge of her prow and gripe, where the stem and keel are joined). Now, when they needed even more extensive repairs, their ability to actually arrive at Greenland was in serious doubt. They had to make their way very carefully to be able to reach Holsteinsborg for repairs.

In early July the George Henry arrived at Holsteinsborg, Greenland. On [July] 15th, with the repairs finished, Buddington headed west hoping to manoeuvre into the pack. But the ice was still too solid to penetrate, so he steered George Henry north, along Greenland’s west coast, hoping to hunt in Disco Bay. Arriving there on 31 July, the hunting was terrible. They only caught halibut and four humpback whales, which yielded the very meagre reward of 184 barrels of oil. [Having begun the voyage on the wrong date, Colby skates over this part of Buddington’s trip. But we do come close to the same information about the whaling being very meager indeed on this trip, though he has the George Henries rendering 188 barrels of oil in June rather than 184 in August.]

Early on 20 August Buddington left Disco and sailed southwest…By late summer the warmer water always flowed up from the south, sweeping north along Greenland’s coast and melting the floe in the eastern part of Davis Strait. The pack ice could still be frozen solid, however, in the middle of the Strait and along Baffin Island’s coast, although Buddington was expecting the summer sun and warmer waters to have begun breaking it up. They made good progress sailing southwestward in open water, covering approximately 50 miles each day for three days. On the 23rd [August] Buddington saw four ships off his starboard bow, solidly frozen in the pack.The following day Buddington lost sight of them…He then boldly steered George Henry into the pack. Over the next few days Buddington manoeuvred approximately 40 miles into it…[on the 28 August] the ice firmed up around George Henry, and two days later they were solidly frozen in…”

Tomorrow I will continue correcting a few points in For Oil, and add some extra information. Still on page 78 of For Oil and Buggy Whips, Colby admits he has conflicting information about when and how Buddington discovered Resolute. Stay tuned!

Carrying on from yesterday’s blog posting we find ourselves on the George Henry and coming up on the memorable day when James Munroe Buddington found the abandoned HMS Resolute. Colby says Buddington was headed home to New London in June when he saw a ship in the distance. In reality it was in August that Buddington headed SW toward home. From my new manuscript:

“They made good progress sailing southwestward in open water, covering approximately 50 miles each day for three days. On the 23rd [August] Buddington saw four ships off his starboard bow, solidly frozen in the pack.The following day Buddington lost sight of them as he continued towards [the SW]. He then boldly steered George Henry into the pack. Over the next few days Buddington manoeuvred approximately 40 miles into it…On the 28th [August] Buddington first saw land…[but then] the ice firmed up around George Henry, and two days later they were solidly frozen in…

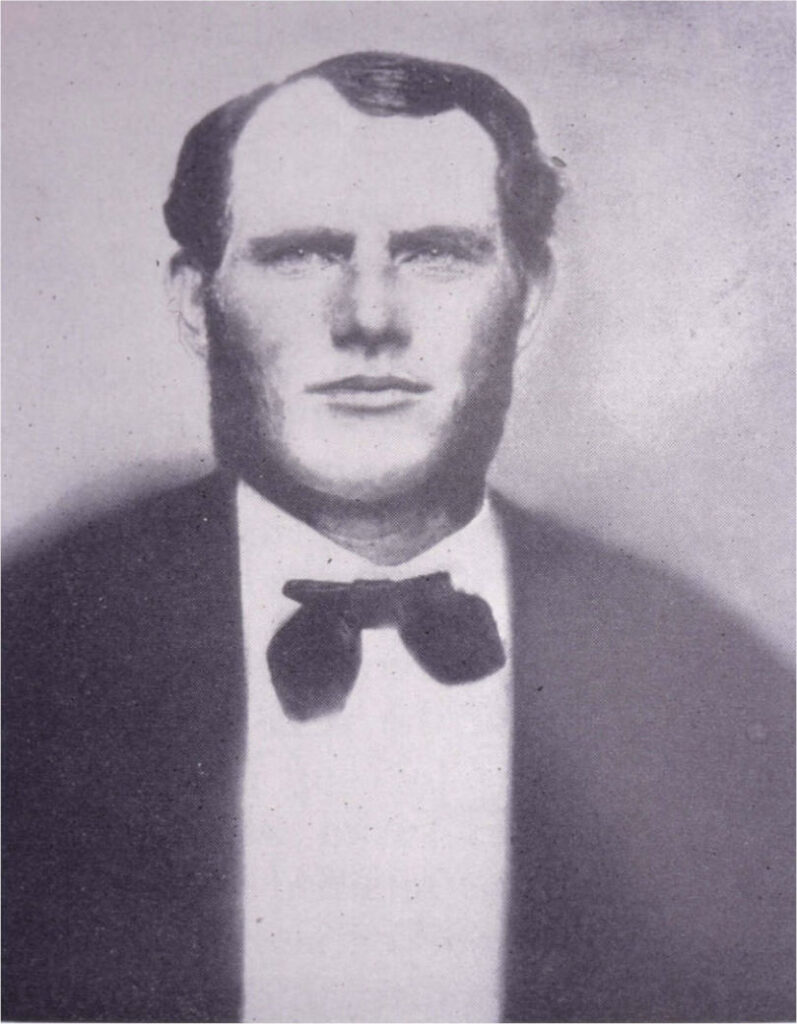

On 10 September…climbing the rigging to examine the state of the ice, Buddington paused halfway to the maintop when he saw a large, three masted ship to the SW, about ten miles away….he suspected she was in distress, because she was almost ashore…was listing badly to port, and he’d received no responses to his repeated signals. If any able-bodied crew were onboard they would’ve responded…”

[The following is an 1855 contemporaneous quote from Buddington which I use in my ms.] ‘We kept gradually nearing one another, although I couldn’t exactly say what caused the thing to come about, except, perhaps the ship may have been struck by a counter current from Davis Straits and driven towards us in that manner. For five days we were in sight of one another and continued to drift toward each other.’

[Colby says on p.78, ‘Captain Buddington maneuvered (sp) the George Henry as near the craft as he deemed advisable, and only his skill prevented his own vessel from being chopped to pieces by the grinding ice of the ice field which surrounded the vessel in the distance.’ This was not correct: the George Henry was already solidly frozen into the pack ice and was drifting with the flow as was the mysterious ship.]

Returning to my ms: “As the movement of the ice brought the ships closer to each other, something in the mystery ship’s rigging made Buddington suspect she was British. But he couldn’t think of any British ship unaccounted for in the vicinity of the Davis Strait. Finally, on the 15th Buddington sent his first mate John T. Quayle, second mate Norris Havens, and two boat steerers, George E. Tyson and Alexander Tillinghurst to investigate. [This is my correction of Colby’s book, wherein he does admit he had found conflicting stories about what happened next.] Tyson claimed 20 years later in his book he saw the ship first, and had to persuade a reluctant Buddington to let men go investigate. He even had to help his shipmates get onto her deck! Perhaps the popularity of the story once the newspapers reported it prompted Tyson to make these false claims. But some of the information he disclosed in the book was accurate, and therefore valuable…

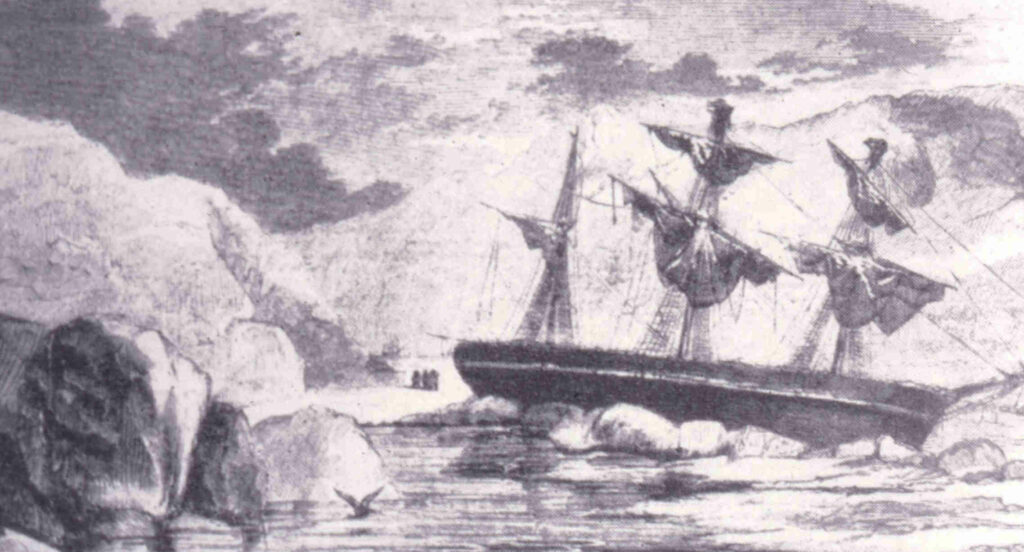

Boarding the mystery ship the George Henries found seven feet of water in her hold, and discovered the heavily ice-encrusted port side exterior was what forced her to list so badly. When they went below they groped their way in the dark until they kicked the captain’s cabin door open and lit some candles. Gazing around they beheld an eerie scene. Decanters and tumblers, still holding wine, were sitting on the table around the mizzen mast, where the captain and his officers had placed them after their last toast before abandoning their gallant ship. Tyson wrote:

‘It was a strange scene to come upon in that desolate place. Some of my companions appeared to feel somewhat superstitious, and hesitated to drink the wine, but my long and fatiguing walk made it very acceptable to me, and having helped myself to a glass, and they seeing it did not kill me, an expression of intense relief came over their countenances, and they all, with one accord, went for that wine with a will; and there and then we all drank a bumper to the late officers and crew …’

As they drank the wine the George Henries glanced around the cabin, and noticed everything: beams, books, clothes, and instruments, were covered in mould. Then the captain’s discarded epaulets on the table shed some light on the mystery ship’s identity: these were the epaulets worn by a British naval officer. Soon, astonishingly, other evidence in the cabin convinced them they were onboard HMS Resolute. But how could she possibly be the same ship that had been abandoned seventeen months ago, and 1,200 nautical miles away? This was incomprehensible! A ship simply couldn’t survived such a journey without divine providence. How had she not been crushed? How had she not run aground? How had she not been smashed against rocky headlands as she rode the current, still encased in ice, through Lancaster Sound and into Davis Strait? As they pondered these mysteries, the George Henries lit a fire in the captain’s stove. The combination of its heat, their exhaustion, the ingestion of much wine and rum caused them to fall into a deep, sound asleep.” At this point our narratives about the salvage of HMS Resolute are in accordance with one another. On page 79 Colby’s account of our gallant ship in the Arctic is again very inaccurate. But that is another topic altogether.